Several types of blowback systems exist within this broad principle of operation, each distinguished by the level of energy derived through the blowback principle and the methods utilized in controlling bolt movement. In most actions utilizing blowback operation, the breech is not mechanically locked at the time of firing: the inertia of the bolt and recoil spring(s), relative to the weight of the bullet, delays opening of the breech until the bullet has left the barrel.[2] A few locked breech designs use a form of blowback (example: primer actuation) to perform the unlocking function.

Other operating principles for self-loading firearms include gas operation, recoil operation, Gatling, and chain. The blowback principle may be considered a simplified form of gas operation, since the cartridge case behaves like a piston driven by the powder gases.[1]

Principle of operation

The blowback system is generally defined as an operating system in which energy to operate the firearm's various mechanisms and provide automation is derived from the movement of the spent cartridge case pushed out of the chamber by rapidly expanding powder gases.[3] This rearward thrust, imparted against the bolt, is a direct reaction of the total reaction to the forward thrust applied to the bullet and the expansion of propellant gases.[3] Certain guns will use all of the energy from blowback to perform the entire operating cycle (these are typically designs using relatively "low power" ammunition) while others will use only a portion of the blowback to operate certain parts of the cycle or simply use the blowback energy to enhance the operational energy from another system of automatic operation.[3]What is common to all blowback systems is that the cartridge case must move under the direct action of the powder pressure, therefore any gun in which the bolt is not rigidly locked and permitted to move while there remains powder pressure in the chamber will undergo a degree of blowback action.[3] The energy from the burnt gases appears in the form of kinetic energy transmitted to the bolt mechanism, which is controlled and used to operate the firearm's operation cycle. The extent to which blowback is employed largely depends on the manner used to control the movement of the bolt and the proportion of energy drawn from other systems of operation.[1] It is with how the movement of the bolt is controlled where blowback systems differ. Blowback operation is most often divided into three categories, all using residual pressure to complete the cycle of operation: simple blowback, advanced primer ignition and delayed blowback or retarded blowback.

Simple blowback

The Colt Model 1908 Pocket Hammerless is a popular example of a simple blowback pistol chambered in .380 ACP. The resistance provided by the mass of the slide alone is enough to delay opening of the chamber until pressure in the barrel has dropped to a safe level.

The cycle begins when the cartridge is fired. Expanding gases from the fired round send the projectile down the barrel and at the same time force the case against the breech face of the bolt, overcoming the inertia of the bolt, resulting in a "blow back" effect. The forces exerted by the powder gases exist for only a relatively brief moment; lingering residual gases continue to act on the case for an even shorter period of time. The breech is kept sealed by the cartridge case until the bullet has left the barrel and gas pressure has dropped to a safe level; the inertia of the bolt mass ensures this.[4] At this point the powder pressure is zero and the force driving the bolt back is also zero, but the case and bolt continue to the rear of their own momentum.[4] As the bolt travels back, the spent cartridge case is extracted and then ejected, and the firing mechanism is cocked while the bolt begins to decelerate against the resistance provided by the recoil or action spring. The bolt eventually reaches a velocity of zero and the kinetic energy from the recoil impulse is now stored in the compressed spring (some energy loss does occur due to friction and the extraction and ejection sequences).[4] The action spring then propels the bolt forward again, which strips a round from the feed system along the way. The bolt carries a new cartridge into the chamber with considerable velocity and the action spring completes its energy transfer just prior to return to battery. The forward velocity is entirely dissipated upon impact with the chamber face.[4]

To remain practical, this system is only suitable for firearms using relatively low pressure cartridges. Pure blowback operation is typically found on semi-automatic, small-caliber pistols, small-bore semi-automatic rifles and submachine guns. Some low-velocity cannon and grenade launchers such as the Mk 19 grenade launcher also use blowback operation.

The barrel of a blowback pistol is generally fixed to the frame and the slide is held against the barrel only by the recoil spring tension. The slide starts to move rearward immediately upon ignition of the primer. As the cartridge moves rearward with the slide, it is extracted from the chamber and typically ejected clear of the firearm. The mass of the slide must be sufficient to hold the breech closed until the bullet exits the barrel and residual pressure is vented from the bore. A cartridge with too high a pressure or a slide with too little mass may cause the cartridge case to extract early, causing a separation or rupture. This generally limits blowback pistol designs to calibers less powerful than 9x19mm Parabellum (.25 ACP, .32 ACP, .380 ACP, 9x18mm Makarov etc.). Any larger and the slide mass starts to become excessive, and therefore few blowback handguns in such calibers exist; the most notable exceptions are simple, inexpensive guns such as those made by Hi-Point Firearms which includes models chambered in .45 ACP, .40 S&W, .380 ACP and 9x19mm Parabellum.[5]

Most simple blowback rifles are chambered for the .22 Long Rifle cartridge. Popular examples include the Marlin Model 60 and the Ruger 10/22. Some blowback rifles or carbines are chambered for pistol cartridges, such as the 9mm Parabellum, .40 S&W and .45 ACP. Examples include the Ruger Police Carbine, Beretta Cx4 Storm, Marlin Camp Carbine and Hi-Point Carbine. There were also a few rifles that chambered cartridges specifically designed for blowback operation. Examples include the Winchester Model 1905, 1907 and 1910. A very unusual blowback rifle was created by fitting the M1903 Springfield rifle with a mechanism called the Pedersen device.

API blowback

Advanced Primer Ignition (API) was originally developed by Reinhold Becker[6] for use on the Becker 20-mm automatic cannon. It became a feature of a wide range of automatic weapons, including the Oerlikon cannon widely used as anti-aircraft weapons during WWII. A simpler form of API blowback is very widely used on submachine guns.In the API blowback design, the cartridge has not been fully chambered and the bolt is still moving forward when the primer ignited. In a plain blowback design, the propellant gases have to overcome static inertia to accelerate the bolt rearwards to open the breech. In an API blowback, they also have to do the work of overcoming forward momentum to stop the forward motion of the bolt. Because the forward and rearward speeds of the bolt tend to be approximately the same, the API blowback allows the weight of the bolt to be halved.[7] Because the momentum of the two opposed bolt motions cancels out over time, the API blowback design results in reduced recoil.

The simplest form of API blowback is used in open bolt submachine guns.[8]In this configuration, the chamber depth is made a few thousandths of an inch shorter than the cartridge case's length. This causes the forward moving bolt's fixed firing pin to ignite the primer a moment before the bolt strikes the chamber face. While this simple version of the API design does not produce very important weight savings, it makes the firing cycle seem smoother to the operator and enhances controllability by reducing the submachine gun's muzzle climb. The heavy telescoping bolt's center of mass is forward of the submachine gun's center of gravity at the point of cartridge ignition. The telescoping bolt's inertial action pushes the submachine gun's muzzle forward and down, thereby reducing felt recoil and countering the recoiling cartridge's attempt to make the muzzle rise.

To make full use of the potential advantages of advanced primer ignition[7], larger calibre APIB guns such as the Becker and Oerlikon use extended chambers, longer than is necessary to contain the round, and straight-sided cases with rebated rims.[8] The last part of forward motion and the first part of the rearward motion of the case and bolt happen within the confines of this extended chamber. As long as the gas pressure in the barrel is high, the walls of case remain supported and the breach sealed, although the case is sliding rearwards. This sliding motion of the case, while it is expanded by a high internal gas pressure, risks tearing it apart, and a common solution is to grease the ammunition to reduce the friction. The case needs to have a rebated rim because the front end of the bolt will enter the chamber, and the extractor claw hooked over the rim therefore has to fit also within the diameter of the chamber. The case generally has very little neck, because this remains unsupported during the firing cycle and is generally deformed; a strongly necked case would be likely to split.

The API blowback design permits the use of more powerful ammunition in a lighter gun that would be achieved by using plain blowback, and the reduction of felt recoil results in further weight savings. The original Becker cannon, firing 20x70RB ammunition, was developed to be carried by WWI aircraft, and weighed only 30 kg.[9] Oerlikon even produced an anti-tank rifle firing 20x110RB ammunition using the API blowback mechanism, the SSG36. On the other hand, because the design imposes a very close relationship between bolt mass, chamber length, spring strength, ammunition power and rate of fire, in APIB guns high rate of fire and high muzzle velocity tend to be mutually exclusive.[8] API blowback guns also have to fire from an open bolt, which is not conducive to accuracy (although for short-ranged submachineguns this is less important) and means they can't be synchronized to fire through a propeller.

Delayed blowback

For more powerful rounds or for a lighter operating mechanism, some system of delayed or retarded blowback is often used, requiring the bolt to overcome some initial resistance while not fully locked. Because of high pressures, rifle-caliber delayed blowback firearms, such as the FAMAS, have fluted chambers to ease extraction. There are various delay mechanisms:Lever delayed

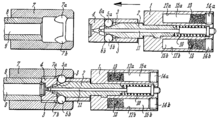

Lever-delayed blowback utilizes leverage to delay the opening of the breech[10]. When the cartridge pushes against the bolt face, the lever moves the bolt carrier rearward at an accelerated rate relative to the light bolt. This leverage significantly increases resistance and slows the movement of the lightweight bolt. John Pedersen patented the first known design for a lever-delay system.[11] The mechanism was adapted by Hungarian arms designer Pál Király (a.k.a. Paul de Kiraly) in the 1930s and first used in the Danuvia 43M submachine gun. Other weapons to use this system are the TKB-517/2B-A-40 assault rifles, the San Cristobal .30 carbine, the FAMAS[12], the BSM/9 M1 submachine gun, B76 pistol, AVB-7.62 rifle and the AA-52 machine gun.Roller delayed

A schematic of the roller-delayed blowback mechanism used in the MP5 submachine gun. This system had its origins in the late-war StG 45(M) assault rifle prototype.

After WWII, former Mauser technicians Ludwig Vorgrimler and Theodor Löffler perfected this mechanism between 1946 and 1950 while working for the French Centre d'Etudes et d'Armament de Mulhouse (CEAM). The first full-scale production rifle to utilize roller-delay was the Spanish CETME followed by the Swiss Sturmgewehr 57, and the Heckler & Koch G3 rifle. The MP5 submachine gun is the most common weapon in service worldwide still using this system. The P9 pistol also uses roller-delayed blowback; however, the Czech vz. 52 is roller-locked.

Gas delayed

Gas-delayed blowback should not be confused with gas-operated. The bolt is never locked, and so is pushed rearward by the expanding propellant gases as in other blowback-based designs. However, propellant gases are vented from the barrel into a cylinder with a piston that delays the opening of the bolt. It is used by Volkssturmgewehr 1-5 rifle, the Heckler & Koch P7, Steyr GB and M-77B pistols.Chamber-ring delayed

When a cartridge is fired, the case expands to seal the sides of the chamber. This seal prevents high-pressure gas from escaping into the action of the gun. Because a conventional chamber is slightly oversized, an unfired cartridge will enter freely. In a chamber-ring delayed firearm, the chamber is conventional in every respect except for a raised portion at the rear of smaller diameter than the front of the chamber. When the case expands in the front of the chamber and pushes rearward on the slide, it is slowed as this raised portion constricts the expanded portion of the case as the case is extracted. The Seecamp pistol operates on this principle.Off-axis bolt travel

John Browning developed this simple method whereby the axis of bolt movement was not in line with that of the bore.[14] The result was that a small rearward movement of the bolt in relation to the bore axis required a greater movement along the axis of bolt movement, essentially magnifying the resistance of the bolt without increasing its mass. The French MAS-38 submachine gun of 1938 utilizes a bolt whose path of recoil is at an angle to the barrel. The Jatimatic and TDI Vector use modified versions of this concept.Toggle delayed

In toggle-delayed blowback firearms, the rearward motion of the breechblock must overcome significant mechanical leverage.[16] The bolt is hinged in the middle, stationary at the rear end and nearly straight at rest. As the breech moves back under blowback power, the hinge joint moves upward. The leverage disadvantage keeps the breech from opening until the bullet has left the barrel and pressures have dropped to a safe level. This mechanism was used on the Pedersen rifle and Schwarzlose MG M.07/12 machine gun. [17] Modern high-pressure blowback systems such as the HK G3 incorporate fluted chambers to facilitate extraction. Lacking fluted chambers, previous toggle-locked firearms required cases lubricated with wax (Pedersen) or oil (Schwarzlose).Hesitation locked

John Pedersen's patented system uses a separate breech block within the slide or bolt carrier. When in battery, the breech block rests slightly forward of the locking shoulder in the frame. When the cartridge is fired, the bolt and slide move together a short distance rearward powered by the energy of the cartridge as in a standard blowback system. When the breech block contacts the locking shoulder, it stops, locking the breech in place. The slide continues rearward with the momentum it acquired in the initial phase. This allows chamber pressure to drop to safe levels while the breech is locked and the cartridge slightly extracted. Once the bullet leaves the barrel and pressure drops, the continuing motion of the slide lifts the breech block from its locking recess through a cam arrangement, continuing the firing cycle. The Remington 51 pistol was the only production firearm to utilize this type of operating system.Tilting bolt

The Reising submachine gun, Models 50 and 55, and semi-automatic carbine Model 60, used a bolt that tilted up into a recess in the receiver. Unlike the fully-locked tilting bolt of the Savage 99 rifle, the Reising bolt was not mechanically locked in position and the action functions as a friction delayed blowback.[18]Screw-delayed

First used on the Mannlicher retarded blowback rifle of 1893, the bolt in screw-delayed blowback was slowed by the need to rotate steeply pitched interrupted threads on the bolt and receiver. John T. Thompson designed a rifle that operated on a similar principle around 1920 and submitted it for trials with the US Army. This rifle, submitted multiple times, competed unsuccessfully against the Pedersen rifle and Garand primer-actuated rifle in early testing to replace the M1903 Springfield rifle.[19] Mikhail Kalashnikov later developed a prototype submachine gun in 1942 that operated by a screw-delayed blowback principle[20], which is also found on the Fox Wasp carbine. A pair of telescoping screws delayed rearward movement of the operating parts during the firing cycle. This weapon was ultimately not selected for production.[21] The screw-delayed action is similar to the Blish lock although Mannlicher's prototype pre-dates the Blish patent.Other blowback systems

Floating chamber

David Marshall Williams (a noted designer for the U.S. Ordnance Office and later Winchester) developed a mechanism to allow firearms designed for full-sized cartridges to fire .22 caliber rimfire ammunition reliably. His system used a small 'piston' that incorporates the chamber. When the cartridge is fired, the front of the piston is thrust back with the cartridge giving a significant push to the bolt. Often described as accelerated blowback, this amplifies the otherwise anemic recoil energy of the .22 rimfire cartridge.[22] Williams designed a training version of the Browning machine gun and the Colt Service Ace .22 long rifle version of the M1911 using his system. The floating chamber is both a blowback and gas operated mechanism.[23]Primer actuated

Primer actuated firearms utilize blowback force to set the primer back to operate a mechanism to unlock and cycle the firearm. John T. Kewish and John Garand were the first to develop the system in an unsuccessful bid to replace the M1903 bolt action rifle.[24] (The U.S. military adopted ammunition with crimped primers that do not set back. Another Garand design was eventually accepted.) AAI Corporation used their developmental piston primer mechanism in a rifle submitted for the SPIW competition.[25] A similar system is used in the spotting rifles on the LAW 80 and Shoulder-launched Multipurpose Assault Weapon use a 9mm, .308 Winchester based cartridge with a .22 Hornet blank cartridge in place of the primer. Upon firing, the Hornet case sets back a short distance, unlocking the action.[26]Limited-utility designs

Blow-Forward

A firearm operation where the barrel is virtually the only moving part of the weapon that is forced forward against a spring by the cartridge pressure and friction of the projectile against the rifling. Only a few weapons such as the Steyr Mannlicher M1894, Schwarzlose Model 1908, Hino Komuro M1908 Pistol, Mk 20 Mod 0 40mm automatic grenade launcher, the Special Operations Weapon and Pancor Jackhammer the last known weapons to use this operation.Blish lock

Main article: Blish lock

The Blish Lock is a breech locking mechanism designed by John Bell Blish based upon his observation that under extreme pressures, certain dissimilar metals will resist movement with a force greater than normal friction laws would predict. In modern engineering terminology, it is called static friction, or stiction. His locking mechanism was used in the Thompson submachine gun, Autorifle and Autocarbine designs. This dubious principle was later eliminated as redundant in the .45 caliber submachine gun. Any actual advantage could also be attained by adding a mere ounce of mass to the bolt.

No comments:

Post a Comment